Crisp and Cruz (2009) have concluded that there is no single definition of peer mentoring as it spans contexts and purposes and is adopted by schools (and other organisations) with different outcomes in mind. Very often people associate peer mentoring with peer tutoring and view it as a platform to enhance academic achievement. Yomtov et al. (2015:2) give a useful working definition: ‘peer mentoring is a process where a mentor provides guidance, support, and practical advice to a mentee who is close in age and shares common characteristics or experiences’. This definition of peer mentoring which involves support beyond the strict limitations of the curriculum is what this article describes.

Peer mentoring can be an empowering process: it can help enhance social competence, build relationships of trust, contribute towards wellbeing, improve educational attainment, reduce negative body image perceptions (Thompson et al. 2012); enhance students’ school self-concept, school citizenship, sense of self and possibility, connectedness, and resourcefulness (Ellis, 2009); and reduce bullying (Coleman et al., 2017), among other benefits. Various national bodies have produced guidelines to formalise the process of peer mentoring and ensure that support is provided both to mentors and mentees (e.g. Northamptonshire Council, Kent Council, West Sussex Council). Here we want to propose a slightly different model, one which is driven and designed by pupils and their desire to ensure that some of the opportunities they were given are passed on to others.

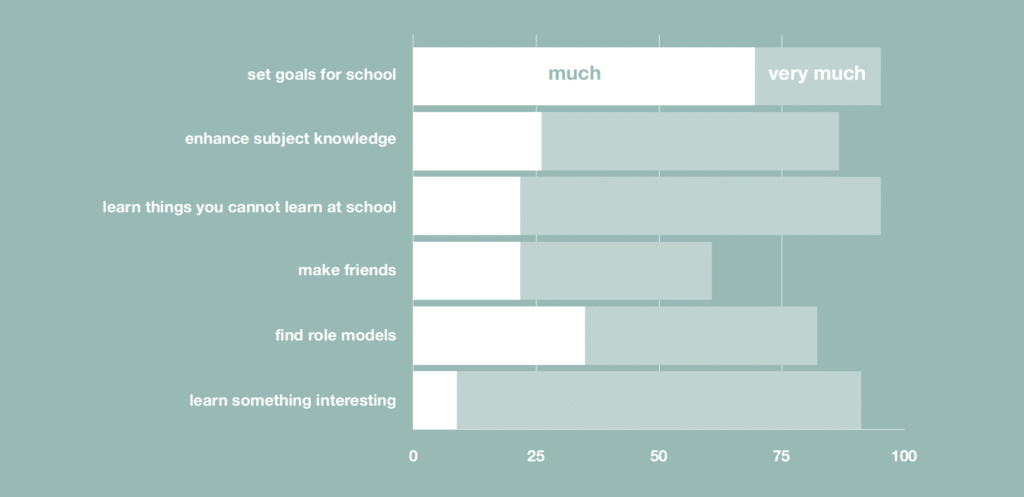

Etonians in Year 12 usually undertake some form of community engagement. This might involve helping in local libraries, keeping clean the local community or doing some tuition with younger pupils from local state schools. Under such an initiative some of the boys did Maths mentoring. They soon realised that beyond the practice tests in Maths and the explanations of Maths problems there was a more important aspect of this project. It was the fact that the pupils across the two schools were benefitting far beyond that. It was a mutual enjoyment and empowerment felt through the mentoring process which made the boys launch the Eton Aspirations Project. The project invited pupils from Holyport College, one of our partner schools, to participate in the project. Term 1 looked into logic and maths problems which required lateral thinking, while term 2 looked into different topics in the social sciences and the arts. These included problems drawn from social psychology, how to set up a business, ethics and moral dilemmas and an introduction to playwriting. This was not a formal course, so pupils could choose when to come as this was on top of their lessons and other extracurricular commitments. We found that the pupils quickly became regulars. Beyond the academic challenge, the project offered them a place to meet friends while discussing interesting topics. This is the summary of what the Year 8 and 9 pupils identified as aspects which they appreciated about the project. There is a combination of elements which made the project successful: academic and social.

Eton boys gave their free time on Tuesday evenings to this. What was in it for them?

Vernon Li

The most important thing I’ve learnt from this experience has been a larger understanding of the way people think. […] While our school has certainly become more diverse, I think that the ‘Eton Bubble’ still, to an extent, holds true.

Most if not all Etonians think very rationally and methodically; but Aspirations is interesting in that our intellectual conversations are being had with students of a different academic level, of differing backgrounds and studying separate syllabuses.

This has been helpful to me when teaching Mathematics or Logic, because of the need to look at problems and empathize with the way our Holyport students progress through thinking stages. In Humanities, it has not only made me more open-minded, but provided our mentors with the fun and sometimes frustrating task of playing devil’s advocate!

For the future, Aspirations has informed my ability to empathize with others and communicate my own vision to them, whether they be my peers, mentors or mentees; and it has helped teach me how to engage people and weld together different ideas in a group setting.

Oscar Bryan

I found what was most beneficial was a further understanding of the subjects I learn in school, by explaining them in depth to people who have often never encountered anything like them before.

By going through the basics of your subjects, you are not only revising these important foundations in a fun way, but simultaneously gain a true appreciation for your own understanding and knowledge of the subject; something which I find is often rare and hard to do in the Eton bubble. Beyond that, it is fulfilling to know that you are actively helping bright young kids participate in discussions and topics they may have otherwise not come across, and know that you are making a positive contribution to their education.

The Project ended in March 2019 when the Holyport pupils gave a short presentation about a topic they chose in front of staff and pupils from Holyport and Eton. We found that a ‘grassroots’ approach to peer mentoring can be a very successful model. The content, although academically interesting, is not the main driver for mentors and mentees to participate in such initiatives. It is mostly the wider experience which pupils enjoy, and this can be at the heart of such mentoring programmes.

References

Coleman, et al. (2017). Peer support and children and young people’s mental Health. Department for Education. Crisp, G., & Cruz, I. (2009). Mentoring college students: A critical review of the literature between 1990 and 2007. Research in Higher Education, 50(6), 525–545.

Ellis, L. A., Marsh, H. W. and Craven, R. G. (2009). Addressing the Challenges Faced by Early Adolescents: A Mixed‐Method Evaluation of the Benefits of Peer Support. American Journal of Community Psychology, 44: 54-75.

Thompson, C., Russell-Mayhew, S. and Saraceni, R. (2012). Evaluating the effects of a peer-support model: reducing negative body esteem and disordered eating attitudes and behaviours in grade eight girls. Eating Disorders, 20(2):113-126.

Yomtov, D., Plunkett, S. W., Efrat, R., & Marin, A. G. (2015). Can Peer Mentors Improve First-Year Experiences of University Students? Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 0(0): 1–20.