In 2012 Professor Sir John Gurdon was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology, for his work with frog cloning that led to a new understanding of DNA.

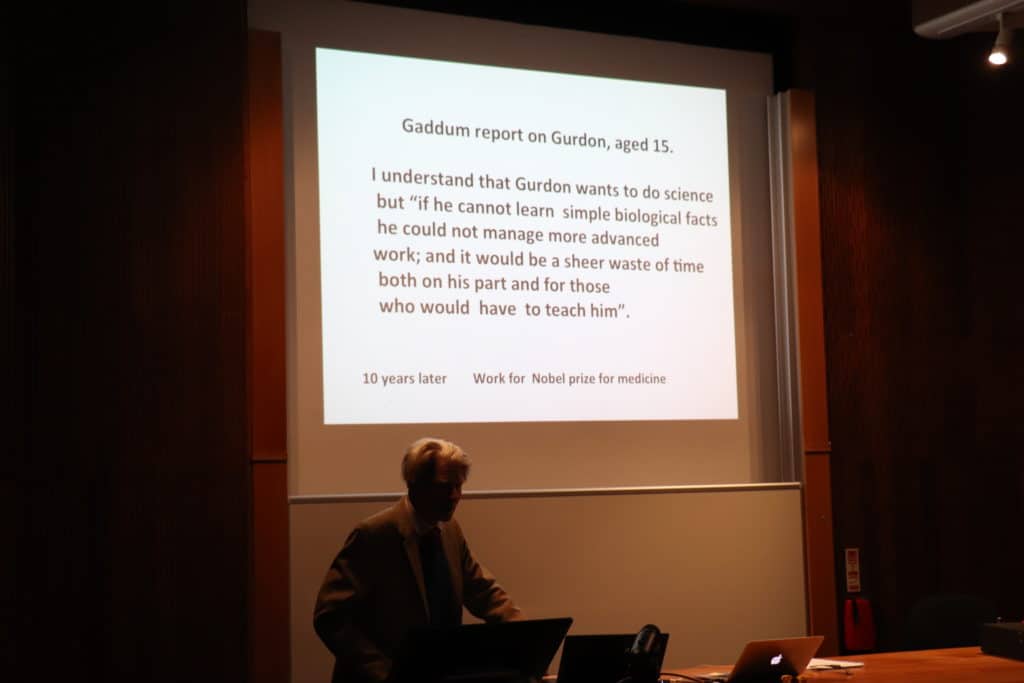

63 years earlier, his biology teacher at Eton College had written a damning report, saying his work was ‘disastrous and far from satisfactory.’ His ambition of becoming a scientist was described as ‘quite ridiculous’, and as he told Eton’s Scientific Society this week, he was kicked out of biology and prescribed Latin and Greek along with others who were hopeless at science!

It was an honour to hear Professor Gurdon, now 88, speak to a packed audience of Eton pupils, teachers, and colleagues from our partnership schools.

He recounted his early fortune working with Dr Michael Fischberg on his PhD project, and his success in producing results which rival teams had struggled to secure.

His doctorate, and subsequent Nobel Prize, were for transplanting adult cells from a frog’s intestine into an egg, which matured and grew into a healthy frog. This, much like the work with Dolly the sheep, showed early proof that every cell in an organism contains the genetic material (DNA) to grow everything an organism needs.

Professor Gurdon told us: ‘Colleagues would have disbelieved me had I been working alone.’ It was through Fischberg’s help, and his technique of using artificially created frogs cells with one nucleus instead of two, that helped validate the work where others had failed.

Professor Gurdon also cloned albino frogs succesfully, and showed that adult cells could be turned into stem cells in just 24 hours incubated in an egg cell. This pertained especially to recent work with rejuvenating old cells, and to the title of the talk: ‘Can we genetically regain our youth?’

Professor Gurdon expanded about the epigenome and histone proteins, to the joy of the biologists in the audience, showcasing a cutting-edge field of research.

Still an active member of the scientific community in the Cambridge lab now bearing his name, Professor Gurdon quoted Confucius, saying, ‘find a job you will love and you’ll never work a day in your life.’

He has no plans to retire, and has a lot of hope for the future of this biological technique along with others, like gene editing. He also told us he had no ethical qualms about such gene editing, and thinks ‘people will be only too glad to eliminate genes carrying crippling disorders,’ citing his colleague Douglas Melton’s work on diabetes.

Professor Gurdon’s parting advice to pupils from Eton and partner schools was: ‘If you want a Nobel prize, work with someone who’s already won one,’ and he advised the teachers in attendance not to be as scathing of someone’s potential as his report card was from his time at Eton.

We are very grateful to hear from one of the greatest scientific minds of the century, and thank Professor Sir John Gurdon for his talk and unique perspective on biology.